Low Profile Amateur Radio: Operating a Ham Station from Almost Anywhere (The Radio Amateur’s Library ; Publication No. 167)

List Price: $ 8.00

Price: [wpramaprice asin=”0872594114″]

[wpramareviews asin=”0872594114″]

Find More Amateur Radio Products

List Price: $ 8.00

Price: [wpramaprice asin=”0872594114″]

[wpramareviews asin=”0872594114″]

Find More Amateur Radio Products

Some cool Amateur Radio images:

2008 Lake County Amateur Radio Club Hamfest

Image by k9mq

Tom, W8FIB

2008 Lake County Amateur Radio Club Hamfest

Image by k9mq

Marty, K9OTR

Some cool Amateur Radio images:

2008 Lake County Amateur Radio Club Hamfest

Image by k9mq

Cliff, WA8ZAZ

List Price: $ 19.95

Price: [wpramaprice asin=”0517558106″]

[wpramareviews asin=”0517558106″]

Find More Amateur Radio Products

Video Rendered and Posted with permission Given by Bill Pasternak WA6ITF youtube.com/va2oz operated by Belair Technologies This Weeks News and Information… AMATEUR RADIO NEWSLINE(tm) REPORT 1790 Released December 2, 2011 IS AVAILABLE RIGHT NOW This Weeks Newscast Anchored By Jim Damron, N8TMW IN THIS WEEKS EDITION FCC SECOND BPL R&O RULES TAKE EFFECT DECEMBER 21 AO-51 GOES QRT ARISSAT-1 APPROACHING LAST DAYS ON-ORBIT NEW ZEALAND HAMS GRANTED POWER INCREASE TO A FULL GALLON ARRL TO RELEASE NEW VIDEO AIMED AT MAKER COMMUNITY ON DECEMBER 27 DAYTON HAMVENTION SOLICITING NOMINATIONS FOR 2012 AWARDS And Much More…

A look back through the years at amateur radio and Christmas…..

Video Rating: 0 / 5

A few nice Amateur Radio images I found:

ALBERTA 1967 amateur radio plate

Image by woody1778a

1967 Amatuer Radio plate with Canada Centennial logo and stylized maple leaf.

ALBERTA 1966 amateur radio plate

Image by woody1778a

ALBERTA 1971 amateur radio plate

Image by woody1778a

Check out these Amateur Radio images:

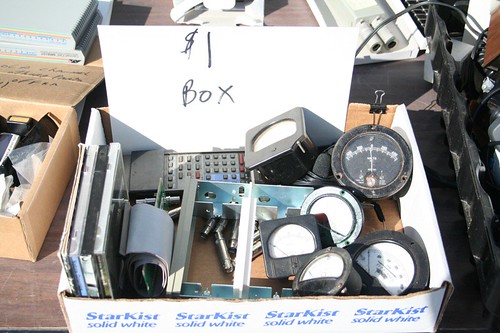

Kennehoochee Amateur Radio Hamfest Finds

Image by The Rocketeer

The Dollar Box

Kennehoochee Amateur Radio Hamfest Finds

Image by The Rocketeer

The artificial horizon display might be good for someone in an earthquake zone…

Video Rendered and Posted with permission Given by Bill Pasternak WA6ITF youtube.com/va2oz operated by Belair Technologies This Weeks News and Information… AMATEUR RADIO NEWSLINE(tm) REPORT 1789 Released November 25, 2011 IS AVAILABLE RIGHT NOW This Weeks Newscast Anchored By Don Wilbanks, AE5DW IN THIS WEEKS EDITION HAM RADIO RESPONDS TO NEVADA WILDFIRE FCC ADOPTS NEW RULES FOR US 5 MHZ OPERATION RSGB BEGINS RESTRUCTURING FOLLOWING EXTRAORDINARY AGM HAMS ASKED TO HELP IN ISS PLASMA EXPERIMENT MEASURE BEFORE CONGRESS MAY HELP INTERNATIONAL HAM-SAT COOPERATION NYC OLD RADIO ROE STILL GOING STRONG – AT ONE SPOT IN BROOKLYN And much more…

Video Rating: 0 / 5

List Price: $ 17.95

Price: [wpramaprice asin=”0130721409″]

[wpramareviews asin=”0130721409″]

Storm Spotting and Amateur Radio

List Price: $ 22.95

Price: [wpramaprice asin=”0872590909″]

[wpramareviews asin=”0872590909″]

Find More Amateur Radio Products

Check out these Amateur Radio images:

amateur radio operator

Image by Mordac

Audioasis on KEXP live from the Sunset, 4/4/2009.

amateur radio operator

Image by Mordac

Audioasis on KEXP live from the Sunset, 4/4/2009.

Smithsonian Amateur Radio NN4SI

Image by edcleve

Worked ’em, and now visited ’em

A few nice Amateur Radio images I found:

amateur radio operator

Image by Mordac

Audioasis on KEXP live from the Sunset, 4/4/2009.

List Price: $ 29.95

Price: [wpramaprice asin=”0070571465″]

[wpramareviews asin=”0070571465″]

[wprebay kw=”amateur+radio” num=”4″ ebcat=”-1″] [wprebay kw=”amateur+radio” num=”5″ ebcat=”-1″]

AMATEUR RADIO NEWSLINE(tm) REPORT 1774 Released August 12, 2011 IS AVAILABLE RIGHT NOW This Weeks Newscast Anchored By Jim Davis, W2JKD This Weeks Top Stories COMMENT PERIOD ON ANCHORAGE VEC LICENSING WAIVER REQUEST CLOSES JUNE 19th SUN EMITS X-CLASS FLARE — COULD AFFECT HF PROPAGATION CANADIAN HAMS MAY GET PERMANENT 60 METER ALLOCATION THIS FALL RAC FORMS TASK FORCE TO EXEMPT ONTARIO HAMS FROM DISTRACTED DRIVING LAW CERTIFICATES OFFERED FOR ASSISTING ARISSAT – 1 ACCIDENTAL DOT STATION LOCATED THROUGH GLOBAL INTRUDER WATCH COOPERATION REFARMING OF SIMPLEX FOR DIGITAL VOICE REPEATERS DEFEATED IN TEXAS – NEW PLAN BEING CONSIDERED NEW ZEALAND CONVICTION FOR SELLING RADIO JAMMERS HAM RADIO READING: THE CHINESE CONNECTION — A CQ EDITORIAL And much

Check out these Amateur Radio images:

Mayor Paul Miller makes Amateur Radio Week Proclamation

Image by GraceFamily

Mayor Paul Miller, Sim Valley California makes Amateur Radio Week Proclamation

Present from Left to Right are Ventura County Amateur Radio Society members: Peter Grace/AI6PG, Steve Curtis/KE6SCS, Denise Curtis/KF6DVG, Kevin Shute/KG6BCL, Peter Heins/N6ZE and Mayor Paul Miller

A very quick look at the NW7US amateur radio station where Tomas (NW7US) is using the JT65-HF software to decode the JT65A weak-signal digital shortwave communications mode of stations from around the world. This is a quick view occurring on the evening of 15 August, 2011. The radio is an Icom IC-7000 transceiver, and the antenna is a Hustler vertical with the 20-meter resonator, mounted on the apartment balcony, on the second floor of the building. More videos on this mode of communication will be posted, which will instruct how to set up the software, and how to carry on a two-way communication with another station, using the JT65-HF software. This video is just a quick glimpse. More info: nw7us.us Please visit my other website, as well: sunspotwatch.com Join us on Facebook: www.facebook.com www.facebook.com Twitter: @hfradiospacewx @NW7US NW7US / NW7US.us

Video Rating: 5 / 5

Roadpro Stainless Steel CB Antenna Stud With SO-239 Connector – Roadpro RP-302.

List Price: $ 2.99

Price: [wpramaprice asin=”B001JT7AJA”]

[wpramareviews asin=”B001JT7AJA”]

Mercer County needs amateur radio operators

Amateur radio operators provide back up communication when the power goes out and can help warn the community about an incoming storm. Right now, Mercer County needs more of them to assist emergency crews. Keith Clark heads up the amateur radio …

Read more on cbs4qc.com

Chronicles the exciting evolution of Amateur Radio from the pioneers who perfected the wireless art through the technical advances of the mid-1930s.

List Price: $ 12.00

Price: [wpramaprice asin=”0872590011″]

[wpramareviews asin=”0872590011″]

[wprebay kw=”amateur+radio” num=”2″ ebcat=”-1″] [wprebay kw=”amateur+radio” num=”3″ ebcat=”-1″]

Ham and the art of communicating

The Indica is now a 'ham shack'. It holds amateur radio equipment that uses certain frequencies for private, wireless communication. Ravishankar tunes the transceiver and we hear Prakasam from Muthumangalam (Erode) who describes the weather in his town …

Read more on The Hindu

ITN TV News Amateur Radio SSTV Report

Essex radio amateur Jeremy Royle G3NOX/G8ACN is featured in this 1981 TV news report about Voyager II pictures of Saturn that were relayed via colour Slow Scan TV (SSTV). Jeremy was one of the pioneers of colour SSTV and on August 20, 1981, …

Read more on Southgate Amateur Radio Club

ARISS ham radio contact planned with 'Marconi' High School in Bari, Italy

On Saturday November 12, 2011 at approximately 09.50 UTC, an ARISS (Amateur Radio on the International Space Station) contact is planned for ISS 'G. Marconi', Bari, Italy. The ISS (High School) "Marconi" was founded in 1940. …

Read more on Southgate Amateur Radio Club

Check out these Amateur Radio images:

Amateur Radio Rig

Image by Joshua Fuller

Love this shot. It came out well considering the lighting conditions.

About the FT-897:

The FT-897D is a rugged, innovative, multiband, multimode portable transceiver for the amateur radio MF/HF/VHF/UHF bands. Providing coverage of the 160-10 meter bands plus the 6 m, 2 m, and 70 cm bands, the FT-897 includes operation on the SSB, CW, AM, FM, and Digital modes, and it’s capable of 20-Watt portable operation using internal batteries, or up to 100 Watts when using an external 13.8-volt DC power source.

ARISS ham radio contact planned for children's hospital in Switzerland

ARISS offers an opportunity for students to experience the excitement of Amateur Radio by talking directly with crewmembers onboard the International Space Station. Teachers, parents and communities see, first hand, how Amateur Radio and crewmembers on …

Read more on Southgate Amateur Radio Club

Space station to Overland High: 'I'm ready to talk to the kids'

Kavya Ganuthula, 12, waits in line to ask astronaut Mike Fossom questions via wireless technology during an Amateur Radio on the International Space Station contact event held Oct. 27 at Overland High School in Aurora. Fossom responded to questions …

Read more on The Aurora Sentinel

Mercer County seeks radio operators to assist in emergencies

The Mercer County Emergency Management Agency is recruiting amateur radio operators to become a part of the Mercer County Amateur Radio Response Team, which will lend support to the Tri-County Medical Response Corps. The amateur radio group will assist …

Read more on Quad City Times

Mercer County ham radio operators needed to assist in emergencies

By Chuck Gysi Mercer County's amateur radio operators are needed to provide communications assistance in emergency and disaster situations. The Mercer County Emergency Management Agency is recruiting hams to become a part of the Mercer County Amateur …

Read more on Aledo Times Record

Local amateur radio club honours 150th birthday of Dr. James Naismith

This occurred nine years later (1900) when Reginald Fessenden – born in East Bolton (Canada's Eastern Townships) – transmitted speech by radio waves. This weekend (Nov. 5-6) the Almonte Amateur Radio Club (AARC) will commemorate the 150th anniversary …

Read more on EMC Almonte/Carleton Place

hamradioireland.blogspot.com This is a short film made by Tony Flynn about amateur radio in Ireland, featuring Thos Caffrey EI2JD and Anthony Murphy EI2KC, filmed at Thos’s QTH in Clogherhead.

Video Rating: 5 / 5

Yaesu FT-847 By Paul Corrigan G4JNN. Artistic images of the Yaesu FT-847 All Mode Amateur Radio Transceiver. www.g4jnn.com www.g4jnn.com www.g4jnn.com www.g4jnn.com

Just received my 2012 MFJ Ham Catalog loaded with new toys for the Amateur Radio Hobbyist.

This is a video I recorded of me operating my amateur (ham) radio station here at my apartment in Englewood, Colorado near Denver during the North American QSO Party Contest (NAQP) on August 21, 2011 (UTC Date) and contacting stations in the contest and the contest exchange was the station call sign, name of operator and US State or Canadian province. I operated on 20 meter SSB voice and I only made 25 contacts in 11 different states or Canadian provinces. My total score was only 275. I could have had a much higher score if I would had spent more time operating on some of the other HF ham bands as well. I was transmitting at a power level of 90 watts and was using a 20 meter 1/4 wave end fed wire antenna hung above my top 3rd floor apartment balcony and was using a 20 meter 1/4 wave length wire for a counterpoise inside my apartment. I have had this Yaesu FT-950 HF rig now for just over a year and have been quite happy with it! It has all kinds of features built in! This is my first HF transceiver I have had since I sold my older Kenwood TS-520S back 1985. The camera I used was a Sony Cyber-Shot DSC-HX1 used in 1080p HD video mode. This video is best viewed in 1080p HD mode here on Youtube if you have a high speed broadband internet connection. Thanks for watching my video and if you are a licensed amateur radio operator, I hope to contact you on the air sometime. 73, Bill, KI7f My home page is at www.ki7f.com Blogging page is at ki7f2.blogspot.com E-mail is: ki7f@yahoo.com

I was first and foremost influenced to make Comm vids by watching one of YankeePreppers video about his experience, which led me to help fill a void at the time and contribute to the prepper/survivalist community. The vid that led me to my YT hobby is: www.youtube.com (explains the Bruce Lee reference at the end.) Yankee talks about the the rabid dogs frothing at the mouth. Now some of them (Douchebags) are getting all upset over my vids without debating their point. Sure is easy to talk crap and run away. I welcome debate, not threats. The 95% of Hams are good people, and an asset to any community, no disrespect to those folks. But you have in every community the 5% of Douchebags that are just plain bad self absorbing assholes.

Video Rating: 4 / 5

Sun City's 'hams' travel the globe with high frequency

By Gwyneth J. Saunders “If that 600-foot antenna in Bluffton goes down in a storm or something, we could be in real trouble when it comes to radio communications in this community," said Bill Gardner, president of the Amateur Radio Club. …

Read more on Savannah Morning News

ISU to host amateur radio presentation

"Amateur Radio is Alive and Well -And Needs You!" will be presented at Indiana State University's Cunningham Memorial Library on Tuesday, Oct. 4 at 7 pm The interactive, hour-long event will provide the basics of amateur radio, also known as ham radio, …

Read more on Indiana State University

Lighthouse in Barcelona: INVISIBLE FIELDS, GEOGRAPHIES OF RADIO WAVES

It's made up of signals that are very familiar, such as television and radio, and signals which are esoteric and enigmatic. It is an ecology that has public spaces – wireless internet and amateur radio – and secret spaces – coded military transmissions …

Read more on Wired (blog)

George W5JDX interviewed me at Leo Laporte’s studio August 20 2011.

Video Rating: 5 / 5

Members keep radio active

Bundaberg Amateur Radio Club president Rusty McGrath is gearing up for the club's 50th anniversary get-together today. THE airwaves have come a long way since the Bundaberg Amateur Radio Club's humble beginnings, operating out of the Red Cross Rooms in …

Read more on Bundaberg NewsMail

Decatur man gets a king to ham it up

Veteran ham operator Lloyd K. Barnett talks frequently to other amateur radio operators from around the world, so he can't recall every name. That's why he maintains four 30-inch-long trays crammed with QSL cards (confirmation or receipt of a call) in …

Read more on The Decatur Daily

Radiosport as a term is sometimes used as two separate words, or as a single word. It refers to the use of amateur radio equipment or the “ham”, in short, as a part of playing some sort of game. It might be group event or a single person event. It can involve other competitors in real time like a race or like a performance or achievement over a given time frame.

The contests are usually sponsored events, and can last anywhere between a few hours and 2 days, the world wide contests being two days usually. It can be local in a specific region, or may involve traveling a long distance. It can be a cumulative contest taking place over many weekends, or a sprint contest which lasts only a few hours. The rules are specific for the event and they include which stations (which regions) may participate and the like.

This is usually called radiosports. This can be any of the following.

Dx-Contest: This is when stations are to make two way contact with as many stations as possible over the longest distance possible. This is called the International DX-Contest today. Awards may be given for the following accomplishments. The “Worked All States Award” if the entrants make contact with someone from every state in the USA. The “Worked All continents Award” is given for making contact with someone from every continent. “Worked All Zones Award” is the same concept with time zones. Other awards include the DX Century Club award, and the UHF/VHF Century Club award.

]]>

Another event is an Amateur Radio Direction finding using radios. A specific number of transmitters needs to be found from a specific region in a map before reaching the end line. This relies on the athletic ability of the ham operator as well as some direction finding skill with radios.

Fox Oaring or Bunny hunting: This is similar to the previous contest but involves more short range equipment of the hams, and so it relies more on the direction finding skills of the contestant rather than the athletic ability. It’s more technical in nature than the previous contest, and the radio can detect signals only 100 meters or so away, so the contestant must locate the transmitter hidden in an area of 200 meter radius.

A more severely restricted game than the Fox Oaring is the Radio orienting contest in compact areas. This requires very high technical skills.

There is another form of the amateur radio direction finding, or bunny hunting, that utilizes transportation with vehicles over long distances. The hams have to travel in their vehicles to the specific region and find the transmitter. Whoever finds the transmitter first and reaches the finish line is the winner. A variation is that the one to find a specific number of transmitters hidden in different places first is the winner. This relies on the traveling skill, orientation skill and the equipment efficiency too.

These events are called ARDF contests, which is short for Amateur Radio Direction Finding Contests. Contests or radiosports are just a part of the hobby activity. Entering contests is not a requirement, but there are many who pursue this almost obsessively, and collect winning certificates by the dozen in fact. On the other extreme are those that are equally passionate about being a ham, but do so purely for communication and satisfaction. The significant thing about hams that needs to be mentioned here is that the hams can and do make regular contact with space stations. Many astronauts are licensed amateur radio operators and use their radios for educational purpose as well as an emergency backup.

So what was once spanning a small region locally in the beginning now has penetrated into space! What was once only Morse code based has now evolved into greater variations involving voice, digital transmission and so on. It is exciting to see how much radio transmission has changed in recent years.

Read about badminton racquets and how to play badminton at Badminton Rules.

List Price: $ 53.23

Price: [wpramaprice asin=”0872597571″]

[wpramareviews asin=”0872597571″]

New TH-UVF1A Dual Band, Dual Display, Dual Standby VHF-UHF 2M/440 deluxe Amateur Handheld Ham radio Transceiver!

* It Features a receive range of 87-108 FM Broadcast, plus 136-174Mhz & 390-520Mhz!

* Transmits full Ham Bands of 144-148Mhz & 430-450Mhz.

*

Direct Keypad entry, VOX, Tone Scan, Voice prompts, FCC Approved.

* 3 selectable colors for the BackLit LCD display!

** Complete Super Radio Package deal includes 120v Drop-in Desktop Rapid charger w/ 2 color l.e.d indica

List Price: $ 189.99

Price: [wpramaprice asin=”B0042FHB7E”]

[wpramareviews asin=”B0042FHB7E”]

[wprebay kw=”amateur+radio” num=”13″ ebcat=”-1″] [wprebay kw=”amateur+radio” num=”14″ ebcat=”-1″]

Construction and naming

With Germany launching their Bremen and Europa into service, the British did not want to be left out in the ship building race. White Star Line began construction on their 60,000 ton Oceanic in 1928, while Cunard planned a 75,000 ton unnamed ship of their own.

Construction on the ship, then known only as “Hull Number 534”, began in December 1930 on the River Clyde by the John Brown & Company Shipbuilding and Engineering shipyard at Clydebank Scotland. Work was halted in December 1931 due to the Great Depression and Cunard applied to the British Government for a loan to complete 534. The loan was granted, with enough money to complete the Queen Mary and to build a running mate, Hull No. 552 which would become the Queen Elizabeth. One condition of the loan was that Cunard would merge with the White Star Line, which was Cunard’s chief British rival at the time and which had already been forced by the Depression to cancel construction on its Oceanic. Both lines agreed and the merger was completed in April 1934. Work on the Queen Mary resumed immediately and she was launched on 26 September 1934. Completion ultimately took 3 years and cost 3 million pounds sterling in total. Much of the ship’s interior was designed and constructed by the Bromsgrove Guild.

The ship was named after Queen Mary, the consort of King George V. Until her launch the name she was to be given was kept a closely guarded secret. Legend has it that Cunard intended to name the ship “Victoria”, in keeping with company tradition of giving its ships names ending in “ia”. However, when company representatives asked the King’s permission to name the ocean liner after Britain’s “greatest queen”, he said his wife, Queen Mary, would be delighted. And so, the legend goes, the delegation had of course no other choice but to report that No. 534 would be called RMS Queen Mary. This story was denied by company officials, and traditionally the names of sovereigns have only been used for capital ships of the Royal Navy. Some support for the story was provided by Washington Post editor Felix Morley, who sailed as a guest of the Cunard Line on the 1936 maiden voyage of the Queen Mary. In his 1979 autobiography, For the Record, Morley wrote that he was placed at table with Sir Percy Bates, chairman of the Cunard Line. Bates told him the story of the naming of the ship “on condition you won’t print it during my lifetime.” The name Queen Mary could also have been decided upon as a compromise between Cunard and the White Star Line, with which Cunard had recently merged, both lines had tradition of using names either ending in “ic” with White Star and “ia” with Cunard.

History (1934-1939)

Queen Mary 1936

There was already a Clyde turbine steamer named Queen Mary, so Cunard White Star reached agreement with the owners that the existing steamer would be renamed TS Queen Mary II, and in 1934 the new liner was launched by Queen Mary as RMS Queen Mary. On her way down the slipway, the Queen Mary was slowed by eighteen drag chains, which checked the liner’s progress into the Clyde, a portion of which had been widened to accommodate the launch.

When she sailed on her maiden voyage from Southampton, England on 27 May 1936, she was commanded by Sir Edgar T. Britten, who had been the master designate for Cunard White Star whilst the ship was under construction at the John Brown shipyard. The Queen Mary had a gross tonnage (GT) of 80,774 tons; her rival, Normandie, which originally grossed 79,280 tonnes, had been modified the preceding winter to increase her size to 83,243 GT (an enclosed tourist lounge was built on the aft boat deck on the area where the game court was), and therefore kept the title of the largest ocean liner. The Queen Mary sailed at high speeds for most of her maiden voyage to New York until heavy fog forced a reduction of speed on the final day of the crossing.

The Observation Bar lounge. The windows were once part of the enclosed Promenade Deck turnaround; the lounge was extended forward after 1967.

The Queen Mary’s design was criticized for being too traditional, especially when the Normandie’s hull was revolutionary with a clipper shaped, streamlined bow. Except for her cruiser stern, she seemed to be simply an enlarged version of her Cunard predecessors from the pre World War I era. Her interior design, while mostly Art Deco, still seemed restrained and conservative when compared to the ultramodern French liner. However, the Queen Mary proved to be the more popular vessel than its larger rival, in terms of passengers carried.

In August 1936, Queen Mary captured the Blue Riband from Normandie, with average speeds of 30.14 knots (55.82 km/h) westbound and 30.63 knots eastbound. Normandie was refitted with a new set of propellors in 1937 and reclaimed the honour, but in 1938 Queen Mary took back the Blue Riband in both directions with average speeds of 30.99 knots (57.39 km/h) westbound and 31.69 knots eastbound, records which stood until lost to the SS United States in 1952.

Interior

The First Class dining room map on the Queen Mary, which tracked the ship’s progress across the Atlantic Ocean.

Onboard amenities on the Queen Mary varied according to class, with First Class passengers accorded the most space and luxury. Among facilities available on board the Queen Mary, the liner featured an indoor swimming pool, salon, ship’s library, children’s nursery, outdoor paddle tennis court, and ship’s kennel. The largest room was the first class dining room (grand salon), which spanned three stories in height and was anchored by wide columns. The indoor swimming pool facility also spanned over two decks in height.

The first class dining room featured a large map of the transatlantic crossing, with twin tracks symbolizing the winter/spring route (further south to avoid icebergs) and the summer/autumn route. During each crossing, a motorized model of the Queen Mary would indicate the vessel’s progress en route.

The First Class dining room on the Queen Mary, also known as the Grand Salon.

As an alternative to the first class dining room, the Queen Mary featured a separate Verandah Grill on the Sun Deck at the upper aft of the ship. The Verandah Grill was an exclusive la carte restaurant with a capacity of approximately eighty passengers, and was converted to the Starlight Club at night. Irish writer and broadcaster, Brian Cleeve spent several months as a commis waiter on the ship in 1938, after he ran away from school. Also on board was the Observation Bar, an Art Deco styled lounge, with wide ocean views.

Woods from different regions of the British Empire were used in her public rooms and staterooms. Accommodations ranged from fully equipped, luxurious first class staterooms to modest and cramped third class cabins. Artists commissioned by Cunard in 1933 for works of art in the interior include Edward Wadsworth and A. Duncan Carse.

World War II

Arriving in New York Harbor, 20 June 1945, with thousands of U.S. troops.

In late August 1939, the Queen Mary was on a return run from New York to Southampton. The international situation led to her being escorted by the battlecruiser HMS Hood. She arrived safely, and set out again for New York on 1 September. By the time she arrived, the Second World War had started and she was ordered to remain in port until further notice alongside the Normandie. In 1940 the Queen Mary and the Normandie were joined in New York by Queen Mary’s new running mate Queen Elizabeth, fresh from her secret dash from Clydebank. The three largest liners in the world sat idle for some time until the Allied commanders decided that all three ships could be used as troopships (unfortunately, the Normandie would be destroyed by fire during her troopship conversion). The Queen Mary left New York for Sydney, where she, along with several other liners, was converted into a troopship to carry Australian and New Zealand soldiers to the United Kingdom. In the conversion, her hull, superstructure and funnels were painted navy grey. Inside, stateroom furniture and decoration were removed and replaced with triple-tiered wooden bunks (which would later be replaced by standee bunks). Six miles of carpet, 220 cases of china, crystal and silver service, tapestries and paintings were removed and stored in warehouses for the duration of the war. The woodwork in the staterooms, the first-class dining room and other public areas were covered with leather. Eventually joined in troop service by the Queen Elizabeth, the two ships were the largest and fastest troopships involved in the war, often carrying as many as 15,000 men in a single voyage, and often travelling out of convoy and without escort. Their high speed meant that it was difficult for U boats to catch them.

On 2 October 1942, Queen Mary accidentally sank one of her escorts, slicing through the light cruiser HMS Curacoa off the Irish coast, with the loss of 338 lives. Due to the constant danger of being attacked by U-Boats, on board the Queen Mary Captain C. Gordon Illingworth was under strict orders not to stop for any reason, the Royal Navy destroyers accompanying the Queen were ordered to stay on course and not rescue any survivors.

The forward section of the Queen Mary was fitted with new big windows and anti-aircraft guns seen here in Long Beach.

In December 1942, the Queen Mary was carrying 16,082 American troops from New York to Great Britain, a standing record for the most passengers ever transported on one vessel. While 700 miles from Scotland during a gale, she was suddenly hit broadside by a rogue wave that may have reached a height of 28 metres (92 ft). An account of this crossing can be found in Walter Ford Carter’s book, No Greater Sacrifice, No Greater Love. Carter’s father, Dr. Norval Carter, part of the 110th Station Hospital on board at the time, wrote that at one point the Queen Mary “damned near capsized… One moment the top deck was at its usual height and then, swoom! Down, over, and forward she would pitch.” It was calculated later that the ship tilted 52 degrees, and would have capsized had she rolled another 3 degrees. The incident inspired Paul Gallico to write his story, The Poseidon Adventure, which was later made into a film by the same name, using the Queen Mary as a stand-in for the SS Poseidon.

During the war, the Queen Mary carried British Prime Minister Winston Churchill across the Atlantic for meetings with fellow Allied forces officials on several occasions, he would be listed on the passenger manifest as “Colonel Warden” and insisted that the lifeboat assigned to him be fitted with a .303 machine gun so that he could “resist capture at all costs”.

After World War II

The Queen Mary in Southampton, June 1956

From September 1946 to July 1947, Queen Mary was refitted for passenger service, adding air conditioning and upgrading her berth configuration to 711 first class, 707 cabin class and 577 tourist class passengers. Following refit, Queen Mary and Queen Elizabeth dominated the transatlantic passenger trade as Cunard White Star’s two ship weekly express service through the latter half of the 1940s and well into the 1950s. They proved highly profitable for Cunard. But in 1958, the first transatlantic flight by a jet began a completely new era of competition for the Cunard Queens. On some voyages, winters especially, Queen Mary sailed into harbour with more crew than passengers. (But she and her sister Queen Elizabeth still averaged over 1000 passengers per crossing into the middle 1960s.) By 1965, the entire Cunard fleet was leaving a trail of red ink. Hoping to continue financing their still under construction Queen Elizabeth 2, Cunard mortgaged the majority of the fleet. Finally, under a combination of age, lack of public interest, inefficiency in a new market, and the damaging after effects of the national seamen’s strike, Cunard announced that both the Queen Mary and the Queen Elizabeth would be retired from service (the Elizabeth would leave service one year later) and were to be sold off. Many offers were submitted, but it was Long Beach, California who beat the Japanese scrap merchants. And so, Queen Mary was retired from service in 1967, while her running mate Queen Elizabeth was withdrawn in 1968. RMS Queen Elizabeth 2 took over the transatlantic route in 1969.

]]>

The Queen Mary in Long Beach

The Queen Mary from the Northern side of Long Beach harbor

After her retirement in 1967, she steamed to Long Beach, California, where she is permanently moored as a tourist attraction. From 1983 to 1993, the Queen Mary was accompanied by Howard Hughes’ Spruce Goose, which was located in a large dome nearby (the dome is now used by Carnival Cruise Lines as a ship terminal, and formerly as a soundstage).

Since drilling had started for oil in Long Beach Harbor, some of the revenue had been set aside in the “Tidelands Oil Fund.” Some of this money was allocated in 1958 for the future purchase of a maritime museum for Long Beach.

Conversion

When the Queen Mary was bought by Long Beach, they decided that the ship would be an iconic host and not for preserving her as an ocean liner. It had been decided to clear almost every area of the ship below C deck (called R deck after 1950 to lessen passenger confusion all the restaurants were on “R” deck) to make way for the museum. This would increase museum space to 400,000 square feet. It required removal of all the boiler rooms, the forward engine room, both turbo generator rooms, the ship stabilisers and the water softening plant. The ship’s now empty fuel tanks were then filled with local mud which would keep the ship’s centre of gravity and draft at the correct levels, as these critical factors had been affected by the removal of all various components and structure. Only the aft engine room and “shaft alley”, at the stern of the ship, would be spared from the cutter’s torch. Remaining space would be used for storage or office space. One problem that arose during the conversion was a dispute between land based and maritime unions over conversion jobs. The United States Coast Guard had final say; the Queen Mary was deemed a building, since most of her propellers had been removed and her machinery gutted. The ship was also repainted with its red water level paint a slightly higher than its old one. During the conversion the funnels were removed as it was the only practical way to lift out the the scrap materials from the engine and boiler rooms, subsiquently it was found that the funnels were held together with over thirty coats of paint and that they had to be replaced with new replica items.

A passageway in First Class accommodation, now part of the onboard hotel

With all of the lower decks nearly gutted from R deck and down, Diner’s Club, the initial lessee of the ship, was to convert the remainder of the vessel into a hotel. Diner’s Club Queen Mary dissolved and vacated the ship in 1970 after their parent company, Diner’s Club International was sold, and a change in corporate direction was mandated amidst the conversion process. Specialty Restaurants, a Los Angeles based company that focused on theme based restaurants, would take over as master lessee the following year.

During this conversion, the plan was to convert most of her first and second class cabins on A and B decks only into hotel rooms, and convert the main lounges and dining rooms into banquet spaces. On Promenade Deck, the starboard promenade deck would be enclosed to feature an upscale restaurant and cafe called Lord Nelson’s and Lady Hamilton’s themed like early 19th century sailing ships. The famed and elegant Observation Bar was redecorated as a western themed bar.

The Queen Mary’s bridge, now open to visitors

The smaller first class public rooms such as the Drawing Room, Library, Lecture Room and the Music studio would be stripped of most of their fittings and converted over to retail space, heavily expanding the retail presence on the ship. Two more shopping malls were built on the Sun Deck in separate spaces previously used for first class cabins and engineer’s quarters.

A post war feature of the ship, the first class cinema, was removed for kitchen space for the new Promenade deck dining venues. The first class lounge and smoking room were reconfigured and converted into banquet space, while the second class smoking room would be subdivided into a wedding chapel and office space. On Sun Deck, the elegant Verandah Grill would be gutted and converted into a fast food eatery, while a new upscale dining venue would be created directly above it on Sports Deck in space once used for crew quarters. The second class lounges would be expanded to the sides of the ship and used for banqueting. On R deck, the first class dining room was reconfigured and subdivided into two banquet venues, the Royal Salon and the Windsor Room. The second class dining room would be subdivided into kitchen storage and a crew mess hall, while the third class dining room would initially be used as storage and crew space. Also on R deck, the first class Turkish bath complex, the 1930s equivalent to a spa, would be removed. The second class pool would be removed and its space initially used for office space, while the first class swimming pool would be used for hotel guests. Combined with modern safety codes, and the structural soundness of the area directly below, the swimming pool is no longer in use.

No crew cabins remain intact aboard the ship today. She now serves as a hotel, museum, tourist attraction, and for rent site for events, but her financial results have been mixed.

The Queen Mary as a tourist attraction

On 8 May 1971, the Queen Mary opened its doors to tourists. Initially, only portions of the ship were open to the public as Specialty Restaurants had yet to open its dining venues or the hotel. As a result, the ship was only open on weekends. In December of that year, Jacques Cousteau’s Museum of the Sea opened, with only a quarter of the planned exhibits built. Within the decade, Cousteau’s museum closed due to low ticket sales and the deaths of many of the fish that were housed in the museum. In November of the following year, the hotel opened its initial 150 guest rooms. Hyatt operated the hotel from 1974 to 1980, when the Jack Wrather Corporation signed a 66-year lease with the city of Long Beach to operate the entire property. Wrather was taken over by the Walt Disney Company in 1988, Wrather owned the Disneyland Hotel, which Disney had been trying to buy for 30 years; the Queen Mary was thus an afterthought and was never marketed as a Disney property.

First Class accommodations on the Queen Mary, converted into a present-day hotel room with modern curtains, bedding and amenities surrounded by original wood paneling, portholes and light fixtures.

Through the late eighties and early nineties, the Queen Mary continued to struggle financially. During the Disney years, Disney planned to develop a theme park on the remaining land. This theme park eventually opened a decade later in Japan as DisneySea, with a recreated oceanliner resembling the Queen Mary as its centerpiece. Hotel Queen Mary closed in 1992 when Disney gave up the lease on the ship to focus on what would become Disney’s California Adventure. The tourist attraction remained open for another two months, but by the end of 1992, the Queen Mary completely closed its doors to tourists and visitors.

In February 1993, under the direction of President and C.E.O. Joseph F. Prevratil, RMS Foundation, Inc began a five-year lease with the city of Long Beach to act as the operators of the property. Later that month, the tourist attraction reopened completely, while the hotel reopened in March. In 1995, RMS’s lease was extended to twenty years while the extent of the lease was reduced to simply operation of the ship itself. A new company, Queen’s Seaport Development, Inc. (QSDI) came into existence in 1995 controlling the real estate adjacent to the vessel. In 1998, the City of Long Beach extended the QSDI lease to 66 years. In 2005, QSDI sought Chapter 11 protection due to a rent credit dispute with the City. In 2006, the bankruptcy court requested bids from parties interesting in taking over the lease from QSDI. The minimum required opening bid was M. The operation of the ship, by RMS, remained independent of the bankruptcy. In Summer 2007, the Queen Mary’s lease was sold to a group named “Save the Queen” managed by Hostmark Hospitality Group, who planned to develop the land adjacent to the Queen Mary, and upgrade, renovate, and restore the Queen Mary. During the time of their management, staterooms were updated with Ipod docking stations and flatscreen TV’s, the ships three funnels were repainted their original Cunard Red color, as well as the ships waterline area, The portside Promenade Deck’s planking was restored and refinished, as well as work on other parts of the ship, many lifeboats were repaired and patched, and the ships kitchens were renovated with new equipment.

In late September 2009, the Queen Mary’s management was taken over by Delaware North Companies, who plan to continue restoration, and renovation of the ship and its property, and work to revitalize and enhance one of the grandest ocean liners of all time.

In 2004, the Queen Mary and Stargazer Productions added Tibbies Great American Cabaret to the space previously occupied by the ship’s bank and wireless telegraph room. Stargazer Productions and the Queen Mary transformed the space into a working dinner theater complete with stage, lights, sound, and scullery.

Meeting of the Queens

On 23 February 2006, the RMS Queen Mary 2 saluted her predecessor as it made its port of call in Los Angeles Harbor, while on a cruise to Mexico. The event was covered heavily by local and international media.

Ship’s horn

The salute itself was carried out with the Queen Mary blowing her one working air horn in response to the Queen Mary 2 blowing her combination of two brand new horns pointing forward and an original 1932 Queen Mary horn (donated by the City of Long Beach) aimed aft. The Queen Mary originally had three whistles tuned to 55 Hz, a frequency chosen because it was low enough that the extremely loud sound of it would not be painful to human ears. Modern IMO regulations specify ships’ horn frequencies to be in the range 70200 Hz for vessels that are over 200 metres (660 ft) in length. Traditionally, the lower the frequency, the larger the ship. The Queen Mary 2, being 345 metres (1,130 ft) long, was given the lowest possible frequency (70 Hz) for her regulation whistles, in addition to the refurbished 55 Hz whistle on permanent loan. 55 Hz is the lower bass “A” note found an octave up from the lowest note of a piano keyboard. The air-driven Tyfon whistle can be heard at least ten miles away.

W6RO

Queen Mary’s wireless radio room

The Queen Mary’s original, professionally manned wireless radio room was destroyed once the ship arrived in Long Beach. In its place an amateur radio room was created one deck above the original radio reception room with some of the discarded original radio equipment used for display purposes only. The amateur radio station with the call sign W6RO (“Whiskey Six Romeo Oscar”) relies on volunteers from a local amateur radio club. They are present most of the time the ship is open to the public, and the radios can also be used by other licensed amateur radio operators.

In honor of his over forty years of dedication to W6RO and the Queen Mary, in November 2007 the Queen Mary Wireless Room was renamed The Nate Brightman Radio Room. This was announced on 28 October 2007 at Mr. Brightman’s 90th birthday party by Joseph Prevratil, President and CEO of the Queen Mary.

Paranormal

The Queen Mary at night, with spotlight on the Soviet submarine B-427

Ghosts were reported on board only after permanently docked in California. Many areas are rumored to be haunted. Reports of hearing little children crying in the nursery room, actually used as the third-class playroom, and a mysterious splash noise in the drained first-class swimming pool are cited. In 1966, 18-year-old engineer John Pedder was crushed by a watertight door in the engine room during a fire drill, and his ghost is said to haunt the ship. There is also said to be the spirit of a young girl named Jackie who was murdered in the pool room haunts the first class pool onboard the ship. It is also said that men screaming and the sound of metal crushing against metal can be heard belowdecks at the extreme front end of the bow. Those who have heard this believe it to be the screams of the sailors aboard the HMS Curacoa at the moment the destroyer was split in half by the liner.

The Queen Mary operates daily paranormal themed tours, some of which have theatrics applied for dramatic effect. The ship maintains a haunted maze and expands to multiple mazes during the Halloween season.

The Queen Mary has been the subject of numerous professional paranormal investigations by printed publications like Beyond Investigation Magazine, nationally televised shows like Ghost Hunters, The Othersiders, and radio’s Coast to Coast AM. The UK paranormal television program, Most Haunted, investigated the ship in a special two-part episode.

On screen

Lists of miscellaneous information should be avoided. Please relocate any relevant information into appropriate sections or articles. (February 2010)

In its permanent berth in Long Beach, the Queen Mary has been used as a filming location for numerous films, television episodes, and commercials. Some examples are:

Assault on a Queen (1966)

The Poseidon Adventure (1972). Some of the Poseidon ship scenes were filmed on board the Queen Mary. A 26-foot long miniature of the ship was used in special effects shots.

Beyond the Poseidon Adventure (1979)

The Gumball Rally (1976). The pier in Long Beach where the ship is located was the finish line for the cross-country race.

S.O.S. Titanic (1979), in which the Queen Mary doubled for her ill-fated predecessor.

Goliath Awaits (1981), About an ocean liner named the Goliath being sunk during World War II and the survivors forming an underwater society.

Someone to Watch Over Me (1987), The murder at the beginning of the film was filmed in the First Class swimming pool area of the Queen Mary.

Toyota’s advertisement for Celica All-trac Turbo in the 1991 Long Beach Grand Prix featured the Queen Mary, with the tagline, “On 14 April, we’re going streaking in front of the Queen.”

Murder, She Wrote (1989), Episode entitled “The Grand Old Lady” takes place on the Queen Mary in 1947.

Bold and the Beautiful (1989)

Tidal Wave: No Escape (1997). Harve Presnell destroys the Queen Mary with an artificial tsunami.

“Triangle,” an episode of The X-Files, featured the Queen Mary as the fictional Queen Anne.

Pearl Harbor (2001).

Escape from L.A. (1996).

Being John Malkovich (1999), parts of the movie were shot on board.

Fiona Apple’s “O’ Sailor” video.

Most Haunted (2005).

The Amazing Race 7 (2005). The starting line for the 7th season.

Airwolf episode “Desperate Monday”.

“Development Arrested”, series finale of Arrested Development (2006).

The ship was used as the home for the finalists of reality TV show Last Comic Standing in the fourth season (2006).

National Lampoon’s Dorm Daze 2 (2006).

The 2007 Cold Case episode World’s End.

The Queen Mary was one location the TAPS crew investigated for hauntings during the second season of the TV series Ghost Hunters.

The Queen Mary was the site of Vincent Chase’s Birthday in the episode “Less Than 30”, of the 3rd Season of Entourage (TV Series).

The Queen Mary is featured on a 2007 Jonas Brothers music video, where they perform their single SOS on the ocean liner.

Portrayed the German liner SS Bremen in the 1983 mini-series The Winds of War based on the 1971 novel by Herman Wouk.

An episode of Quantum Leap took place on the Queen Mary.

The 1997 romantic comedy Out to Sea (with Jack Lemmon and Walter Matthau) used the Queen Mary as filming location.

The Queen Mary was the set of “The Search for the Next Elvira”, where many hopeful young women contended to be the next “Mistress of the Dark”.

Miss America: Countdown to the Crown (2009), a reality competition show; part of the precompetition for the Miss America 2009 pagent.

An episode of New York Goes to Work used the Queen Mary as a filming location (2009).

The Othersiders (2009), The team investigated here for paranormal activity.

Legally Blondes (2008).

In popular culture

This “In popular culture” section may contain minor or trivial references. Please reorganize this content to explain the subject’s impact on popular culture rather than simply listing appearances, and remove trivia references. (February 2010)

The album title for Apologies to the Queen Mary by Wolf Parade references an incident on the ship in which the band was involved.

Most of the series finale of Arrested Development takes place on the ship.

The music video of the Jonas Brothers song SOS was filmed aboard the Queen Mary.

A season one episode of Moonlight features the Queen Mary as the location of a murder of a stalked Hollywood star.

The Queen Mary is referenced in episode 7 of the ABC Family series The Middleman, “The Cursed Tuba Contingency”. One of the episode’s villains has a ship which he boasts is “three feet longer than the Queen Mary, and eighty-six feet longer than the Titanic.” In reality, the Queen Mary (at 965 feet perpendiculars) really is eighty-three feet longer than the Titanic (at 882 feet).

In the book The Miraculous Journey of Edward Tulane, the Queen Mary plays a major part as the start of Edward’s Journey. Edward, a china rabbit, is on the Queen Mary with his owner, a little girl named Abileine. Two boys accidentily throw Edward overboard, and the rabbit starts out on his journey. The Queen Mary is referenced in the text and in a painting in the book.

In Tim Powers’s book Expiration Date, the Queen Mary plays a significant part, related to the supernatural legends above.

See also

“It’s Men that Count”; late 1930s promotional poster for the Cunard Line

RMS Mauretania (1938)

RMS Queen Elizabeth

RMS Queen Elizabeth 2

MS Queen Elizabeth

RMS Queen Mary 2

MS Queen Victoria

References

Notes

^ Royal Lady – The Queen Mary Reigns in Long Beach

^ The Bromsgrove Guild – an illustrated history, The Bromsgrove Society

^ a b c Maxtone-Graham, John. The Only Way to Cross. New York: Collier Books, 1972, p. 288

^ “Chains brake liner at launching”. Popular Science. 1934-12. http://books.google.com/books?id=uigDAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA20&lpg=PA20#v=onepage&q=&f=false. Retrieved 2009-11-02.

^ Atlantic Liners: RMS Queen Mary

^ ocean-liners.com SS Normandie

^ Bruce, Jim, Faithful Servant: A Memoir of Brian Cleeve Lulu, 2007, ISBN 978-1-84753-064-6, (pp.50-55)

^ Modern art takes to the waves

^ The Historic Queen Mary – RMS Foundation, Inc.

^ Levi, Ran. “The Wave That Changed Science”. The Future of Things. http://thefutureofthings.com/column/1005/the-wave-that-changed-science.html. Retrieved 2009-11-02.

^ Lavery, Brian. Churchill Goes to War: Winston’s Wartime Journeys. Naval Institute Press, 2007, p. 213.

^ OceanLiners.com. RMS Queen Mary

^ Harvey, Clive (2008). R.M.S. Queen Elizabeth-The Ultimate Ship. Carmania Press. ISBN 9780954366681.

^ The Queen Mary. The Queen Mary’s History

^ Long Beach Report. A REPORT ON THE QUEENSWAY BAY DEVELOPMENT PLAN AND THE LONG BEACH TIDE AND SUBMERGED LANDS. State Lands Commission, April 2001

^ Tibbies Cabaret. History. Retrieved on August 8, 2009.

^ USATODAY.com – Queen Mary 2 to meet original Queen Mary in Long Beach harbor

^ ‘Queen Mary’s horn (MP3) – PortCities Southampton

^ The Funnels and Whistles

^ Welcome to kockum sonics: Tyfon IMO regulations

^ “The voice of the Queen Mary can be heard ten miles away” (JPG image)

^ W6RO – Associated Radio Amateurs of Long Beach

^ Human Touch Draws Ham Radio Buffs, Gazettes Newspaper

^ The wireless installation on RMS Queen Mary

^ Chisholm, Charlyn Keating. “Haunted Hotel – Queen Mary Hotel in Long Beach, California”. About.com. http://hotels.about.com/od/hauntedhotelsatoz/p/hau_queenmary.htm. Retrieved 2008-11-25.

^ Winer, Richard, Ghost Ships

^ Queen Mary – Attractions at Night QueenMary.com

^ Queen Mary’s Shipwreck – Annual Halloween fest

^ http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7VUZK-D5czs&feature=related

Bibliography

The Cunard White Star Quadruple-screw North Atlantic Liner, Queen Mary. – Bonanza Books, 289 p., 1979. – ISBN 0517279290. Largely a reprint of a special edition of “The Shipbuilder and Marine Engine-builder” from 1936.

Cunard Line, Ltd., John Brown and Company archives.

Clydebank Central Library Clydebank, Scotland.

Roberts, Andrew, Masters and Commanders: How four titans won the war in the West, 1941-1945, Harper Collins e-Books, London

External links

Wikimedia Commons has media related to: RMS Queen Mary

Website of current commercial operator (Event listings as well as Facts & History section)

Queen Mary Alternative Visions (Describes the construction and conversion of the Queen Mary and advocates its partial restoration)

Time Magazine: The Queen; 11 August 1947

The Great Ocean Liners: RMS Queen Mary

Clydebank Restoration Trust

RMS Queen Mary at Chris’ Cunard Page (The Last Great Atlantic Fleet)

Coordinates: 334511 1181123 / 33.7531N 118.1898W / 33.7531; -118.1898

Records

Preceded by

Normandie

Holder of the Blue Riband (Westbound)

1936 1937

Succeeded by

Normandie

Atlantic Eastbound Record

1936 1937

Holder of the Blue Riband (Westbound)

1938 1952

Succeeded by

United States

Atlantic Eastbound Record

1938 1952

v d e

Cunard ships

Current Fleet

RMS Queen Mary 2 (2004) MS Queen Victoria (2007)

Planned

MS Queen Elizabeth (2010)

Former Ships

RMS Britannia (1840) RMS Persia (1856) SS Abyssinia (1870) SS Servia (1881) RMS Etruria (1884) RMS Umbria (1884) RMS Campania (1892) RMS Lucania (1893) SS Ivernia (1899) RMS Carpathia (1903) RMS Carmania (1905) RMS Caronia (1905) RMS Lusitania (1907) RMS Mauretania (1907) RMS Franconia (1910) RMS Ascania (1911) RMS Albania (1911) RMS Ausonia (1911) RMS Laconia (1912) RMS Alaunia (1913) (1913) RMS Aquitania (1913) SS Orduna (1914) SS Empire Barracuda (1918) RMS Albania (1920) RMS Antonia (1921) RMS Ausonia (1921) RMS Scythia (1921) RMS Andania (1922) RMS Berengaria (1922) RMS Laconia (1922) RMS Lancastria (1922) RMS Majestic (1922) RMS Ascania (1923) RMS Aurania (1924) SS Letitia (1924) RMS Alaunia (1925) RMS Carinthia (1925) SS Laurentic (1927) RMS Britannic (1929) RMS Georgic (1934) RMS Olympic (1934) RMS Queen Mary (1936) RMS Mauretania (1939) SS Pasteur (1939) MV Empire Audacity (1939) RMS Queen Elizabeth (1940) SS Empire Battleaxe (1943) SS Empire Broadsword (1943) SS Valacia (1943) RMS Media (1947) RMS Caronia (1949) RMS Saxonia (1954) RMS Ivernia (1955) RMS Carinthia (1956) RMS Sylvania (1957) RMS Alaunia (1960) RMS Queen Elizabeth 2 (1967) MS Cunard Adventurer (1971) MS Cunard Ambassador (1972) MS Cunard Countess (1975) MS Cunard Princess (1976) MS Sagafjord (1983) MS Caronia (1983) MS Royal Viking Sun (1994)

v d e

U.S. National Register of Historic Places

Keeper of the Register History of the National Register of Historic Places Property types Historic district Contributing property

List of entries

National Park Service National Historic Landmarks National Battlefields National Historic Sites National Historical Parks National Memorials National Monuments

Categories: Art Deco ships | Blue Riband holders | Clyde-built ships | Landmarks in Los Angeles, California | Ocean liners | Museum ships in California | Passenger ships of the United Kingdom | National Register of Historic Places in California | Rogue wave incidents | Ships of Scotland | Ships of the Cunard Line | Ships on the National Register of Historic Places | Steamships | Visitor attractions in Long Beach, California | Troop ships of the United Kingdom | 1934 ships | Museums in Long Beach, California | Haunted attractions | Paranormal placesHidden categories: Articles with trivia sections from February 2010 | All articles with trivia sections

I am Frbiz Site writer, reports some information about door shoe rack , wooden storage chest.

Related Amateur Radio Articles